The Dehumanisation of Cypriots

In order to subjugate a population, British colonists favoured the model of stripping agency, puppeteering local leaders and manufacturing conflict to fabricate divide in order to weaken collective capacity for resistance. What made a community so syncrectic, so vulnerable to micro-nationalisms?

As always, a disclaimer: this text is my interpretation of events. I am by no means a geo-political expert, however, my lens reveals the ways in which coloniality is produced and re-produced. In an effort to decolonise Cyprus, we cannot reproduce that coloniality. So, let's look at some already existing stories..

Drawing on Edward Said’s Orientalism, which exposes how Western powers manufacture reductive identities to legitimise domination, I want to examine how Cypriots were stripped of their political agency and reduced to mere agents of Enosis (union with Greece) and Taksim (partition) during the mid-20th century. These binaries, engineered by British and American imperial interests and enforced by local political elites (i.e. Denktaş's false flag bomb) facilitated Cyprus’s division while suppressing grassroots efforts for unity, such as the buried example of ‘Operation Harvest’.

Colonial Fabrication of the "Cypriot Other"

Under British rule (1878–1960), Cyprus was governed through divide-and-rule tactics. The colonial administration institutionalised ethnic divisions, erasing centuries of shared cultural ties. By the 1950s, anti-colonial movements were co-opted into competing nationalist projects: Greek Cypriots were portrayed as irrationally fixated on Enosis, while Turkish Cypriots were depicted as natural proponents of Taksim. This reductionism, akin to Said’s “Orientalist” discourse, denied Cypriots the agency to envision a unified future.

The 1963–64 intercommunal violence, often misrepresented as an inevitable ethnic conflict, overshadowed fleeting moments of solidarity. As documented in Commander Packard’s account of the Tripartite Patrols, Operation Harvest—a joint Greek and Turkish Cypriot effort to harvest crops during ceasefire intervals—demonstrated the potential for cooperation. Farmers from both communities collaborated to salvage crops, bypassing militarized checkpoints and ethnically segregated zones. This grassroots initiative, however, was systematically suppressed. U.S. Secretary of State George Ball, prioritising Cold War stability and NATO’s strategic control over Cyprus, dismissed such efforts as “naïve” and counterproductive to partition plans. Packard, in conversation regarding these patrols, recalled Ball saying “But you've got it wrong son. Hasn't anyone told you that our target here is for partition?”.

Anglo-American policymakers feared communal unity would undermine their narrative of “incompatible” ethnic identities, which justified NATO’s intervention and the island’s militarization. With the report of Operation Harvest being “lost”, one may wonder if it would have survived if it fit the narrative necessary for ‘74 to occur.

Media as a Weapon of Division

Colonial and post-colonial media amplified everyday tensions—such as a Greek Cypriot securing a job over a Turkish Cypriot—as existential clashes between nationalisms. British outlets framed employment (and romantic) disputes as evidence of “Greek aggression” or “Turkish obstructionism,” erasing systemic colonial inequities. Issues could not simply be a man vs a man, it had to be an intercommunal conflict caused by ethnic divergence rather than a simple, boring, human problem.

Operation Harvest’s suppression was similarly obscured; media ignored cross-ethnic cooperation, instead amplifying violence to legitimise foreign “peacekeeping.” The ‘Times of Cyprus’ reduced the operation's pragmatism to “temporary truces,” reinforcing the myth that Cypriots could not coexist without imperial oversight.

Cold War Machinations and the London-Zurich Farce

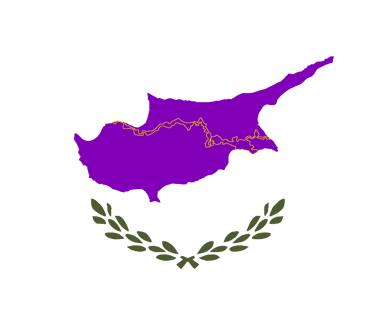

The 1959 London-Zurich Agreements embedded ethnic partition into Cyprus’s constitution while retaining British bases. The U.S, viewing Cyprus through a Cold War lens, pressured Archbishop Makarios to abandon non-alignment. Secretary Ball's dismissal of communal initiatives ensured Cyprus remained a fractured NATO outpost. The 1964 Green Line partition, enforced by British forces, physically codified dehumanisation, reducing communities to geopolitical pawns.

Neo-Colonial Legacies

Cyprus’s 1974 partition solidified under Turkish occupation, a testament to imperial realpolitik. The UK’s bases (colonies) still operate extraterritorially, while the U.S. and EU treat the island as a migration buffer zone. The suppression of Operation Harvest epitomizes how decolonial resistance was stifled; today, bi-communal projects remain marginal in peace talks dominated by ethnonationalist frameworks.

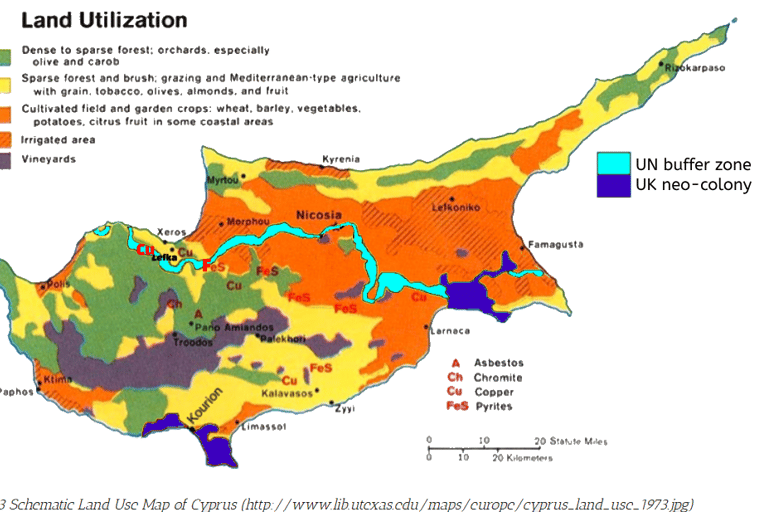

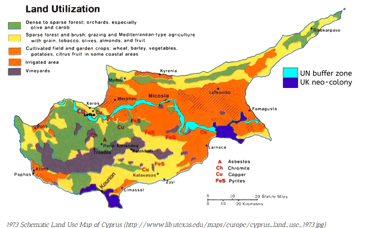

The proof is in the muhallebi - The Green Line's demarcation happens to correlate with the Cyprus Mines Corporation (CMC), a U.S owned company who dominated copper extraction since 1916's mining sites, particularly in northern Cyprus. After Cyprus’s 1974 partition, CMC’s primary mines (e.g., at Lefka/Mavrovouni), critical to global supply chains, fell on the Turkish Cypriot side of the Green Line. This suggests the line may have been drawn to secure resource-rich zones under Turkish control, aligning with Cold War-era Western interests in maintaining access to minerals.

While no explicit documentation links the Green Line’s coordinates to mining maps, the geographical overlap between the line and CMC’s operational sites implies economic motivations in its delineation. This division hindered cross-zone cooperation, consolidating resource exploitation under partitioned governance.

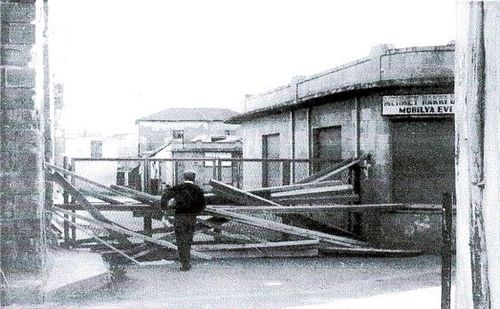

The official narrative is, the Green Line was literally drawn under two distinct historical contexts, with different actors involved. First, British General Peter Young, commander of the UN peacekeeping force in Cyprus, sketched the initial demarcation in December 1963 during intercommunal violence. He reportedly used a green pencil on a map, giving the line its name.

The line expanded upon the Clemens Line from 1956, separating Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot neighbourhoods in Nicosia to halt clashes following existing conflict zones, such as barricaded streets and strategic positions held by both communities. After Turkey’s military intervention in July 1974 (and subsequent invasion in August), the line expanded into a 180-km buffer zone across the entire island, enforced by Turkish forces advancing southward. The division reflected military territorial gains by Turkish forces, which occupied ~37% of Cyprus, including key cities like Kyrenia, Famagusta, and parts of Nicosia. The line was not based on administrative districts but on ethnic demographics and strategic control. The line followed natural terrain (e.g., rivers, hills) and existing ceasefire positions to minimise friction. Supposedly, the buffer zone’s width (from a few meters to 7 km) aimed to prevent direct contact between opposing forces.

However, this is now having the opposite effect. The Buffer Zone covers ~3% of Cyprus’ land, including fertile agricultural areas. Farmers on both sides lost access to fields within the zone, disrupting livelihoods and reducing agricultural output, functioning as economic control. For example, Greek Cypriot farmers near Deryneia have clashed with UNFICYP over restrictions on cultivating land close to the ceasefire line. Isolated populations and restricted access to arable land and solar farms occupied by the UN have increasingly caused more and more friction as time goes on, as the status quo of the island proves unsustainable for local populations. Not to mention Avdimou became the first neighbourhood powered entirely by solar energy, not the buffer zone. Initiatives like bi-communal projects (e.g., solar energy cooperation) are limited in scale and fail to address systemic distrust. This perpetuates the long-lasting stripping of Cypriot agency in order to force the island to adhere to an externally determined narrative, reducing capacity to dictate our own organically.

Institutionalizing Micro-nationalisms

British colonial education policies systematically dismantled Cypriots’ multilingual, hybrid identities. Schools were segregated by language—Greek Cypriots were taught Katharevousa (purist Greek), while Turkish Cypriots learned Ottoman Turkish infused with Kemalist reforms. This linguistic engineering, as analysed by Rebecca Bryant in The Past in Pieces (2010), erased the shared Cypriot dialect (Kypriaka) peppered with Turkish, Arabic, and Armenian loanwords—a living testament to centuries of coexistence.

Post-1955, curricula became battlegrounds for nationalist indoctrination. Greek Cypriot textbooks mapped Cyprus as “unredeemed Hellenic land,” while Turkish Cypriot materials depicted the island as an “extension of Anatolia.” As noted by historian Andrekos Varnava, British officials like Governor Hugh Foot actively approved these divisive syllabi, dismissing bilingual education proposals as “impractical.” The colonial state thus produced generations psychologically alienated from their neighbours, primed for partition.

The 1960 Constitution’s Article 173 institutionalised dehumanisation by requiring separate communal rolls for voting, effectively banning cross-ethnic political parties. As AKEL’s Nicos Koshis lamented in 1963 parliamentary debates, this “ethnic mathematics” reduced Cypriots to demographic statistics, criminalizing class-based or secular alliances. Even marriage across communities became bureaucratically punitive: Greek-Turkish couples had to renounce one spouse’s communal rights, a policy retained until 2015.

This legal framework enabled external powers to manipulate ethnic quotas. When the U.S. Embassy pressured President Makarios in 1964 to “respect Turkish Cypriot autonomy,” they weaponised Article 173 to fracture labour unions and agricultural cooperatives that had united Greek and Turkish Cypriot workers against British/American mining corporations like CMC.

Dehumanisation reached its zenith through state-tolerated paramilitary violence. British forces routinely released EOKA and TMT prisoners near opposing communities’ neighbourhoods, as documented in declassified War Office memos (1964–67). These orchestrated provocations—like the infamous 1967 Kofinou/Köfünye incident, where Greek Cypriot police clashes with Turkish Cypriot farmers were staged by TMT operatives wearing EOKA bandanas—engineered a climate of existential terror.

As psychologist Vamik Volkan observed, such trauma bonding created “chosen glories” and “chosen traumas” that replaced lived memories with nationalist mythologies. By the 1970s, children on both sides could recite lists of “martyrs” but knew nothing of Harvest-era crop-sharing or AKEL’s joint May Day rallies. Today, it is better known that the British eradicated malaria, instead of Mehmet Aziz, Turkish Cypriot health official, who actually did it without dehydrating our land.

An example of class-based cross communal solidarity: Kavazoğlu and Mishaoulis

The story of Derviş Ali Kavazoğlu and Kostas Mishaoulis directly challenges the colonial and nationalist binaries that reduced Cypriots to agents of Enosis or Taksim. Their lives—and deaths—embody the anti-colonial solidarity systematically erased to sustain imperial exploitation.

Both men were activists in AKEL (Progressive Party of Working People), a once-upon-a-time communist party advocating for a unified, independent Cyprus free from British colonialism and partition (at least it did in 1962 and changed their goals to Enosis in 64). Kavazoğlu and Mishaoulis rejected the ethnic reductionism of Enosis and Taksim, instead organising across communal lines. Their collaboration exemplified Said’s critique of Orientalism—they refused to be confined to colonial constructs of “Greek” or “Turk,” asserting a shared hyphenated-Cypriot identity rooted in class struggle.

In 1965, both were assassinated by TMT, the Turkish Cypriot nationalist group backed by Turkey. These killings were not random acts of “ethnic violence” but targeted political executions designed to crush leftist resistance to partition. Their assassinations followed years of threats from nationalist groups, which operated with tacit British and NATO tolerance.

The British colonial administration and later NATO-aligned powers viewed AKEL’s multi-ethnic mobilisation as a threat to their divide-and-rule strategies. By framing Kavazoğlu and Mishaoulis’ deaths as “intercommunal strife,” colonial media obscured the political motives behind their killings. This narrative served to legitimise the Green Line partition (1964) and later NATO-backed interventions, reinforcing the myth that Cypriots were “naturally” divided.

Mainstream Cypriot histories, dominated by ethnic nationalism, marginalised their story. Kavazoğlu and Mishaoulis were recast as footnotes to the “real” conflict between Greek and Turkish nationalisms, their solidarity buried like Operation Harvest—another suppressed example of communal cooperation. This erasure mirrors the dehumanising logic critiqued by Said, where colonial subjects are denied complex identities beyond their assigned roles in imperial scripts.

Kavazoğlu and Mishaoulis’ story disrupts the dehumanizing narratives that enabled Cyprus’s partition. Their resistance underscores how colonial and Cold War powers weaponised ethnic binaries to fracture class solidarity, ensuring the island remained exploitable. Remembering them is an act of decolonial defiance—one that rejects the imposed identities of Enosis and Taksim, and reclaims Cyprus as a site of shared struggle.

Toward a Decolonial Cyprus

Rejecting Orientalist binaries requires centering suppressed histories like Operation Harvest and Kavazoğlu & Mishaoulis. These moments reveal Cypriots’ capacity for solidarity, buried under imperial narratives of “ancient hatreds.” Dismantling partition demands confronting its architects: the British bases, NATO’s and the EU's strategic hegemony, and the media myths that dehumanise Cypriots as perpetual agents of Enosis or Taksim. Only then can Cyprus reclaim its sovereignty—not as a pawn of empires, but as a mosaic of shared struggle and resilience.