Nobody in Cyprus is 'free'

We live under multiple occupations, including the illusion of 'freedom' offered to those living in RoC controlled areas. This manufactured autonomy leaves us vulnerable to further class domination

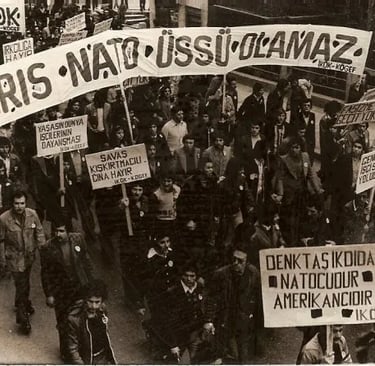

First of all, can we stop starting our modern history at 1974. For Turkish Cypriots, the division started in 1958. Furthermore, none of us are ‘free’. The only thing that makes somebody more ‘free’ in the south, than somebody in the north, is privilege. The RoC’s ‘democracy’ is just embarrassing by de-jure standards instead.

We can’t fix a problem that we refuse to diagnose.

Whitewashing our respective roles in the divide of our island only serves to relieve actors of accountability. An honest diagnosis assigns responsibility to multiple actors - and reveals the ways in which social voids are filled by imperial powers e.g. the TRNC functioning as a Turkish puppet state and replacing what should have always been the RoC’s role for Turkish Cypriots, or the incessant scapegoating of migrants to address the corruption-induced cost of living.

Revisiting Cyprus’ Divided History: The Politics of Selective Memory

The dominant narrative framing Cyprus’ modern history through the lens of 1974—the year of Turkey’s military intervention—obscures deeper structural tensions rooted in anti-colonial struggles, competing nationalisms, and the failure of bicommunal governance. As Kalliopi Geronymaki’s work on Greek Orthodox advocacy (1950–1960) demonstrates, the seeds of partition were sown long before 1974, with both Greek and Turkish Cypriot leaderships prioritising ethnonationalist agendas over shared sovereignty. This text re-examines the island’s history through a critical lens, challenging reductive binaries while interrogating the role of memory, education, and international intervention in perpetuating division.

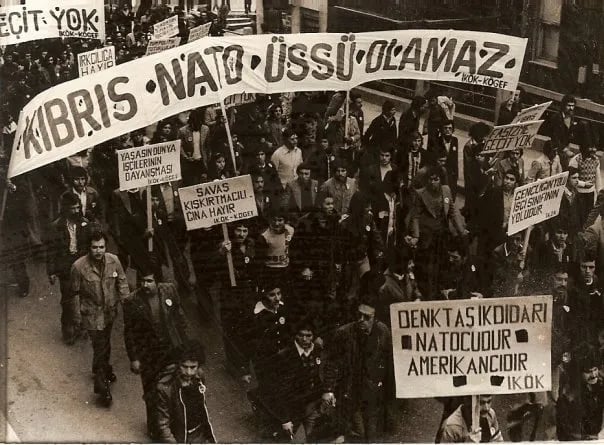

The 1950s saw Greek Cypriot Orthodox elites, including Archbishop Makarios III, strategically aligning anti-colonial rhetoric with the pursuit of Enosis (union with Greece), a goal explicitly at odds with British colonial interests and Turkish Cypriot fears of marginalization (Geronymaki, 2023). However, this period also witnessed the emergence of Turkish Cypriot counter-mobilizations, including early demands for Taksim (partition). These were not merely Turkish state impositions but also grassroots responses to systemic exclusion. Leftist Turkish Cypriot intellectuals like Dedecay (founder of first University in the North) framed Taksim as a protective measure against existing and potential violence, reflecting a growing distrust in Greek Cypriot leadership’s commitment to power-sharing. Whether or not one agrees with the declaration of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), it can certainly be understood as a consequence of the RoC’s consistent refusal to engage with turcophone Cypriots with political equity.

Neither community entered the 1960 Republic of Cyprus in good faith. Taksim gained momentum as an imperial solution to a human reaction of ghettoisation. While Makarios publicly embraced bicommunalism, he privately courted Enosis well into the 1960s, mirroring Turkish Cypriot leaders’ tacit support for partition. This mutual intransigence rendered the RoC inherently unstable, a “state without a nation” (Bryant, 2004).

The intercommunal violence of 1963–64 marked a point of (literally) no return. Turkish Cypriots were forced into enclaves, deprived of political representation and basic resources, then supplemented by their ultranationalist response TMT, while Greek Cypriot ultranationalists—emboldened by the junta in Greece—escalated attacks on Turkish Cypriot villages (Kızılyürek, 2019). The 1967 Kofinou clashes further entrenched segregation, with Ankara threatening intervention to prevent the perceived ethnic cleansing.

The 1964 Johnson Letter, often cited as proof of U.S. restraint on Turkey, also underscores the severity of Turkish Cypriot displacement. By 1974, over 25,000 Turkish Cypriots had been internally displaced, a figure overshadowed in post-1974 narratives fixated on Greek Cypriot displacement (Hatay, 2005). Such narratives often attempt to attribute all Turkish Cypriot displacement to Turkey, instead of the pursuit of Enosis.

Turkey’s military intervention in July 1974—triggered by the Athens-backed coup against Makarios—is frequently depicted as an imperialist land grab, which it absolutely was. However, the August 1974 invasion followed the collapse of Geneva talks, where Greek Cypriot leaders rejected Turkish demands for a bizonal federation (Hannay, 2005). While Turkey’s actions in August indeed violated international law, they also reflected a calculated response to decades of insecurity that assigns responsibility to multiple actors. We have no way of knowing what would have happened to Turkish Cypriots if the Turkish military hadn’t intervened, but we do know what was happening before.

The post-1974 establishment of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) in 1983 emerged from Turkish Cypriots’ political limbo. Isolated by the RoC and the international community, the TRNC initially built a functional welfare state, albeit dependent on Turkish aid (Lacher & Kaymak, 2005). Conversely, the RoC’s admission to the EU in 2004—despite rejecting the Annan Plan for reunification—rewarded Greek Cypriot intransigence while deepening Turkish Cypriot disillusionment (Loizides, 2014).

Greek Cypriot education systems perpetuate a “phantom limb” nationalism, framing the north as occupied territory while erasing Turkish Cypriot agency (Papadakis, 2005). This paternalism undermines reconciliation efforts, as seen in the RoC’s refusal to recognize TRNC institutions even for humanitarian purposes. Conversely, Turkish Cypriot narratives often downplay Ankara’s authoritarian influence, including settlement policies that altered the north’s demographics (Human Rights Watch, 2014). Yet, of course they would. Efforts to integrate Turkish Cypriots into the RoC are performative at best and highly conditional at worst. How can Turkish Cypriots be expected to expel their occupier, when the alternative [RoC] is hardly an attractive option? It is not just propaganda that makes Cypriots feel unsafe - but lived realities. This fear is weaponised by agents of nationalist agendas, yes, but fear doesn't magically appear from nowhere. It was built over years of exclusion, violence, and broken promises - including the accession to the EU while Turkish Cypriots remain stateless, economically dependent upon their authoritarian occupier while socially alienated from their kin. This isolation left Turkish Cypriots even more primed for Turkish interventionism, where cultural institutions face existential threats and fragment our cultural integrity.

Both communities now face converging crises: the RoC has among the EU’s lowest wages and weakest welfare provisions, while the TRNC grapples with economic collapse and Erdogan-era authoritarianism. Minority communities—Armenians, Maronites, and migrants—remain marginal in both polities, their histories subsumed by ethnonationalist discourse (Trimikliniotis, 2018).

Reunification requires reckoning with shared culpability. Rather than bickering over whether a state that clearly does exist for the North of the island, and wields the power to enact the violence of a state, can we nurture conditions for actual change? Can we acknowledge our current reality instead of wishful pseudo-thinking? Greek Cypriots must confront the legacy of Enosis-driven exclusion, while Turkish Cypriots acknowledge Ankara’s destabilizing role and further manipulation of our trauma to suit a turanist narrative. As Avi Khalil argues, progressive alliances across the Green Line—centered on class and anti-racism rather than ethnonationalism—offer a path forward. Greek Cypriots should not long for a status quo that Turkish Cypriots were already experiencing violence within. Calls for a unified Cyprus under the EU and RoC umbrella often reproduce the very conditions of exclusion they claim to oppose. This demands rejecting the RoC’s “internationally recognised” paternalism and replacing the TRNC’s dependency on Turkey, fostering grassroots solidarity.

Cyprus’ tragedy lies not in 1974 alone but in decades of mutually reinforcing nationalist fantasies. As Geronymaki’s work reminds us, only by dismantling these myths can the island’s communities forge a future beyond partition. Our identity is not tied to a nation-state, nor to a language.

It’s time to center the experience of those most impacted by the policies of our island, and guess what.. They’re not just Cypriots, but the Black and brown migrants whose dehumanising treatment is the result of the Cypriot reluctance to de-centre our victimhood. It is our responsibility to design a ‘state’ with a representative class, race and gendered analysis.

References

- Bryant, R. (2004). Imagining the Modern: The Cultures of Nationalism in Cyprus.

- Geronymaki, K. (2023). A Front for ‘Humanity’: Greek and Greek Cypriot Orthodox Advocates Between Anti-colonialism, Self-determination and Enosis (1950–1960).

- Hannay, D. (2005). Cyprus: The Search for a Solution.

- Hatay, M. (2005). Beyond Numbers: The Politics of Population in Cyprus.

- Kızılyürek, N. (2019). Cyprus: The End of a Conflicted Island.

- Lacher, H., & Kaymak, E. (2005). Transforming Identities: Beyond the Politics of Non-Settlement in North Cyprus.

- Loizides, N. (2014). Negotiating the Cyprus Problem.

- Papadakis, Y. (2005). Echoes from the Dead Zone: Across the Cyprus Divide.

- Trimikliniotis, N. (2018). Racism and new migration to Cyprus: The racialisation of migrant workers.