British colonial environmental policies

Resistance, legacy, and ecological consequences in the context of British colonies

This article is not to rid local actors of their role in environmental degradation. In order to avoid reproducing coloniality, we need to understand how it was implemented in the first place, so that we may resist its agents. Current tensions between renewable energy projects and local communities, particularly in occupied territories, are critiqued for perpetuating colonial dynamics and undermining local voices. Let’s learn how to see it in action.

“Planting on the peninsula had modest beginnings: in 1893 the Commissioner of Limassol, Roland L. N. Michell, had “ventured [...] to suggest the formation of a plantation near the Akrotiri salt marsh, with a view to sanitary results [...]. A beginning has just been made, on a very small scale. About four thousand cuttings (of plane, willow, poplar, and olive) have been planted in a diminutive enclosure [...] and I am promised [...] that provision will be made for carrying on the project, by the planting of eucalyptus and other suitable trees” (House of Commons 1896, p. 61)

When Sir Garnet Joseph Wolseley and colonial officers of the British Empire disembarked at the port of Limassol in 1878, reshaping of the island’s environmental and agricultural landscapes through policies rooted in Eurocentrism began. Framed as corrective measures against perceived degradation, these interventions prioritised scientific forestry and cash crops while marginalizing indigenous practices. The ‘uncivilized’ local inhabitants fit the bill for a defining feature of British rule in the semi-arid environments. Any Cypriot that could not be cast for this role in the imperial play, were conversely described as active destroyers of the landscape (Harris, 2007).

Colonial Environmental Policies and Implementation

‘Forward-thinking British foresters taught the residents to adopt what they viewed to be worthwhile, productive... lifestyles... [emphasis added]. They also taught the people to respect and appreciate nature’ (Harris, 2012).

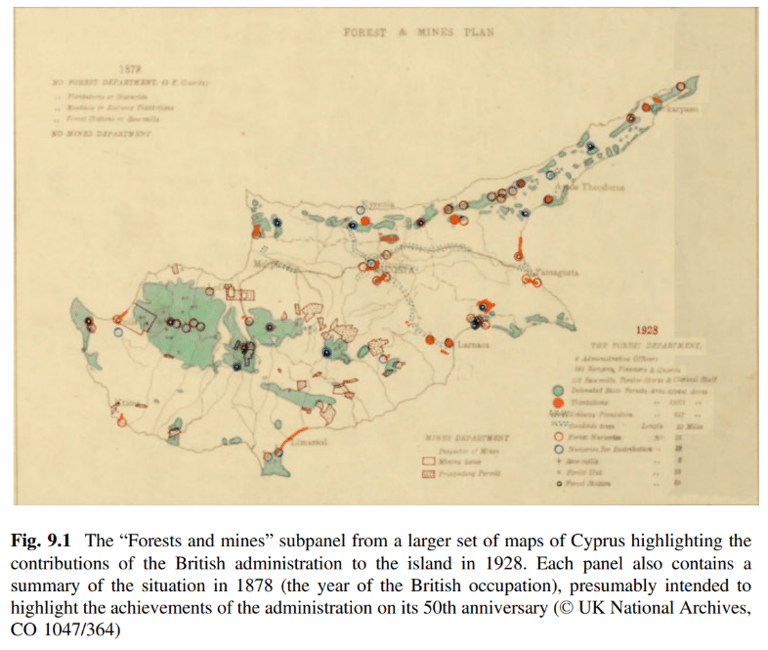

The British administration introduced forest conservation laws, afforestation projects, and agricultural reforms to align Cyprus’s ecology with imperial interests. Drawing on practices honed in India and Australia, officials targeted perceived inefficiencies in Ottoman and local land use. Reforestation efforts focused on non-native species like eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus), lauded for their rapid growth and soil stabilisation properties (Davis, 2019). The Forest Law of 1913 criminalised traditional practices such as goat grazing and woodcutting, enabling state control over 20% of Cyprus’s land by 1930 (Dietzel, 2014). Agricultural reforms promoted cash crops like tobacco, displacing subsistence farming and eroding food sovereignty.

Resistance to Colonial Policies

Local communities resisted these policies through everyday defiance and organised protests. Harris (2018) documents how villagers engaged in clandestine grazing, sabotage of eucalyptus saplings, and destruction of forest boundary markers—acts framing environmental policies as extensions of colonial oppression. These efforts were rooted in economic necessity and cultural preservation, as British restrictions threatened agro-pastoral systems refined over centuries.

Organised resistance emerged in regions like the Akrotiri Peninsula, where land seizures for afforestation sparked protests. Harris (2018) highlights the 1923 uprising in the Troodos foothills, where communities rejected grazing permits and clashed with forest guards. Similarly, the destruction of boundary cairns in Mesaoria symbolised rejection of colonial land demarcation (Given, 2002). While these actions delayed plantation expansion in some areas, colonial repression through fines, arrests, and livestock confiscation often quashed dissent.

Ecological and Agricultural Impacts

The imposition of eucalyptus and golden wreath wattle (acacia saligna) has profound ecological consequences:

Water scarcity: Extensive plantations lowered water tables in arid regions like Mesaoria, exacerbating droughts.

Biodiversity loss: Monocultures outcompeted endemic species like Cyprus cedar (Cedrus brevifolia), creating ecological “dead zones” (Terra Cypria, 2012).

Soil degradation: Eucalyptus leaf litter’s high tannin content disrupted soil microbiology, countering erosion control goals (Davis, 2019).

Fire risk: Flammable oils in eucalyptus increased wildfire frequency, a legacy persisting today (Younes et al, 2024). Wildfires are also catalysed by the displacement of native fire-resistant flora.

The British weaponised the island’s vulnerability to malaria to extend their control and justify further eucalyptus monocultures. Due to the draining effect of these plantations, there was no hesitation to take credit for Cyprus being free from malaria by the 1950s. Meanwhile, the story of Mehmet Aziz and his team is censored by Rockefeller archives. Alongside malariologist Marshall Barber, Aziz studied mosquito control efforts across Syria and Palestine. Drawing on Fred Soper and Bruce Wilson’s Rockefeller-funded research in Brazil and Egypt, he later implemented his malaria eradication plan (Khalil, 2023) However, this was not Aziz’s only legacy. He argued that labour contracts must reflect the value of the work. Why would the team want to eradicate malaria if their contracts ends when they do? Stay tuned for a documentary produced by Avi Khalil Betz-Heinemann, detailing what we can learn from the 1940s campaign.

Anyway, agricultural shifts toward cash crops weakened traditional practices, resulting in epistemic loss. Tobacco and cotton replaced drought-resistant carob and olive cultivation, increasing reliance on irrigation and fertilisers. While colonial policies boosted export revenues, they entrenched soil depletion and water scarcity, challenges still faced by Cypriot farmers (Dietzel, 2014).

Legacy and Contemporary Challenges

Post-independence Cyprus retained colonial-era laws, including the Forest Law, which continues to prioritise state-controlled conservation over community-based management (Dietzel, 2014). Modern eradication programs targeting invasive eucalyptus struggle with the species’ resilience, particularly in protected areas like the Akamas Peninsula (Terra Cypria, 2012).

In the north, Özdemir (2024) indicates that individuals with a strong intrinsic religious orientation tend to exhibit a greater sense of connectedness to nature. Demonstrating this tension between organic and imported attitudes, Khalil Avi Betz-Heinemann and Joseph Tzanopoulos (2020) argue that corvid culling practices reflect a broader organisational pattern influenced by colonial legacies, where the management of wildlife is framed as a form of "harvesting and husbandry". This approach is characterised by the use of "scarecrows" and "scapegoats," where corvids are scapegoated for the failures of wildlife management, allowing organizations to maintain their authority and control over the landscape.

Scholars like Naylor (2023) argue that decolonising environmental governance requires integrating traditional knowledge, such as seasonal grazing and native agroforestry. Recent initiatives have revived heirloom crops and limited prescribed burning, yet policy frameworks remain dominated by colonial-era paradigms (Harris, 2018). This analysis is shared by Khalil and Tzanopoulos, noting that the British colonial administration sought to transform local practices into a structured system of control, which has evolved into the current practices of the 'TRNC'. Administrative processes, such as the production of hunting maps and regulations, serve to reinforce the legitimacy of the hunting federation while failing to address the ecological complexities of the landscape. The ongoing culling of corvids upholds the imperial imported “clean” landscape narrative, resulting in a cycle of waste production and ineffective management practices that ultimately detract from the ecological health of the region.

Successes and Failures of Resistance

Resistance efforts achieved partial successes: clandestine grazing preserved some traditional practices, and organised protests delayed land seizures in regions like Akrotiri. However, the broader failure to halt afforestation or repeal restrictive laws underscored the power imbalance between colonisers and communities. Harris (2018) notes that resistance nonetheless forged a collective anti-colonial consciousness, later galvanizing the EOKA movement (1955–1959) in its push for 'independence'.

"The laws, economic structures and cultural basis for European colonialism didn’t disappear when nations gained independence in the mid-20th century" (Ross, 2019). Decolonisation is the complete rejection of the outdated idea that “civilized Europeans” were entitled to dominate the “uncivilized”.

British Green Colonialism

The legacy of British colonial environmental policies persists in former (officially anyway) colonies through enduring land management systems, resource extraction patterns, and institutional frameworks. These historical interventions continue shaping ecological and socioeconomic realities across multiple continents.

1. India's Forest Governance

The 1865 Indian Forest Act established state control over woodlands, displacing indigenous communities while creating timber reserves and replacing food crops with cash crops. This model evolved into modern joint forest management systems, where 22% of India's territory remains state-controlled forests despite constitutional recognition of tribal rights. The colonial-era distinction between "productive" and "waste" lands still influences land categorisation. The British cut down most oak and deodar forests for commercial purposes, then replaced those native forests — which were resistant to wildfires — with large-scale pine plantations for procuring resin. Every summer, dry pine needles are responsible for massive wildfires in several parts of the Indian Himalayas.

2. West African Plantation Economies

In Nigeria and Ghana, colonial cash-crop systems transformed into today's oil palm monocultures. The Niger Delta's petroleum extraction infrastructure, initially developed by Shell-BP (founded under colonial charter in 1937), continues operating through partnerships with post-independence governments, perpetuating environmental degradation patterns documented since the 1950s (Wood, 2015). The people of the Niger Delta, while dealing with the entirety of the consequences resulting from the $500 billion dollars of oil extracted, have seen a very small portion of that money come back to them in terms of infrastructure development and compensation for environmental damages (Obi, 2008).

3. Malaysian Land Tenure

Palm oil trees were introduced to British Malaya by the British government in early 1870s as ornament plants from Nigeria. The government focused on increasing its palm oil output by rapidly increasing the land area for palm oil cultivation. This deforestation directly led to the Great Flood of December 1926 and by the 1920s over 2.1 million acres of land had been deforested by the Empire in Malaya (Hagan, 2005). British rubber plantation policies (1877-1910) established land title systems prioritising commercial agriculture over native customary rights. Modern Malaysia retains this framework, with 5.8 million hectares of oil palm plantations – a direct continuation of colonial land-use priorities.

4. Caribbean Infrastructure

In Hong Kong, colonial water management policies (1894-1929) that prioritised urban centers over rural areas established patterns of centralised resource allocation. These patterns manifested in similar urban-biased infrastructure models which persist in Caribbean nations like Jamaica, where 92% of water systems follow colonial-era distribution networks. Colonial-era land distribution patterns established through 19th-century grants (like the 1834 Peter Daly allocations) still influence property rights and rural land use. Some pre-independence laws regulating land ownership remain codified despite calls for reform.

5. Settler-Colonial Landscapes

Canada's 1876 Indian Act and Australia's terra nullius doctrine created enduring property systems marginalizing First Nations. Though formally repealed, these frameworks still influence resource extraction permits, with 72% of Canada's oil sands projects operating on traditional indigenous lands.

The UK's modern environmental policies like the Climate Change Act 2008 increasingly address these legacies through climate reparations funding, yet former colonies remain locked in resource-export roles established under imperial trade networks.

Decolonization efforts now confront the challenge of rewriting legal and ecological systems designed for extraction rather than sustainability.

Similarly, the Levant region's environmental challenges remain deeply intertwined with British colonial legacies, particularly through imposed borders, resource management systems, and agricultural practices that persist in modern governance structures:

1. Border Creation & Transboundary Water Conflicts

The 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement's artificial borders divided watersheds and tribal territories, creating modern water disputes. For instance, 60% of the Jordan River Basin's flow is still allocated through colonial-era agreements favouring Occupied Palestine and Jordan, marginalizing Palestinian access. This framework perpetuates regional water inequities rooted in British-French territorial engineering.

2. Jordan's Tribal Land Tenure Systems

British Mandate policies (1921-1946) formalised tribal land ownership in Transjordan to streamline taxation and control. These registrations now hinder modern water conservation efforts, as 72% of Jordan's communal lands operate under colonial-era ownership frameworks that resist centralised groundwater management (Hartnett, 2024).

3. Urban-Rural Water Infrastructure

In mandate Palestine (1920-1948), British authorities developed water systems prioritising Jewish settlements and cities like Haifa over rural Arab communities. This template continues in Lebanon and Syria, where 68% of water infrastructure investments target urban centers, replicating colonial spatial inequalities (Shamir, 2022).

4. Forest Management & Conflict

British afforestation projects in the Galilee (1930s) aimed to "secure wastelands" against Bedouin pastoralism, employing invasive pine species that increased wildfire risks. Modern Occupied Palestine and Lebanese reforestation programs retain this ecological approach, heightening tensions with indigenous communities over land use (Holtermann, 2025).

While postcolonial states have nominally reformed these systems, the Levant's climate adaptation strategies remain constrained by institutional frameworks designed for resource extraction rather than ecological balance. Recent droughts and desertification patterns trace directly to colonial disruptions of traditional water-sharing practices and agro-pastoral systems. Decoupling environmental policy from its imperial origins remains pivotal for regional climate resilience.

British colonial environmental policies reveal the tensions between imperial ecological visions and local realities. While reforestation and agricultural reforms left a legacy of biodiversity loss and soil degradation, resistance efforts highlighted the resilience of indigenous knowledge. Addressing these colonial imprints demands centering local epistemologies in conservation—a critical step toward equitable environmental governance.

References

Betz-Heinemann, KA and Tzanopoulos, J. 2020. Scarecrows and Scapegoats: The Futility and Power of Cleaning a Landscape. Worldwide Waste: Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 3(1): 9, 1–9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/wwwj.33

Davis, J., Moulton, A.A., Van Sant, L. and Williams, B., 2019. Anthropocene, capitalocene,… plantationocene?: A manifesto for ecological justice in an age of global crises. Geography Compass, 13(5), p.e12438.

Dietzel, I., 2014. The ecology of coexistence and conflict in Cyprus: exploring the religion, nature, and culture of a Mediterranean island (Vol. 57). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

Given, M., 2002. Maps, fields, and boundary cairns: Demarcation and resistance in colonial Cyprus. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 6, pp.1-22.

Hagan, J., Wells, A., 2005. The British and rubber in Malaya, c1890-1940. University of Wollongong. Conference contribution. https://hdl.handle.net/10779/uow.27794391.v1

Harris, S.E., 2007. Colonial forestry and environmental history: British policies in Cyprus, 1878–1960. The University of Texas at Austin.

Harris, S.E., 2012. Cyprus as a Degraded Landscape or Resil-ient Environment in the Wake of Colonial Intrusion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(10): 3670–75.

Hartnett, A.S., 2024. After the Commons: Economic Opportunity and Colonial Legacies of Land Privatization.

Holtermann, M.E., Plonski, S., (2025) Making All Deserts Bloom: The Racist Space/Time of UAE-Israel Collaboration, Geopolitics, 30:2, 859-894, DOI: 10.1080/14650045.2024.2398241

Naylor, L.A., Dungait, J.A., Zheng, Y., Buckerfield, S., Green, S.M., Oliver, D.M., Liu, H., Peng, J., Tu, C., Zhang, G.L. and Zhang, X., 2023. Achieving sustainable Earth futures in the Anthropocene by including local communities in critical zone science. Earth's Future, 11(9), p.e2022EF003448.

Obi, C., 2008. Oil Extraction, Dispossession, Resistance, and Conflict in the Oil-Rich Niger Delta. Nordic Africa Institute.

Shamir, R., 2022. ‘Contested infrastructures: the case of British-mandate Palestine’, Settler Colonial Studies, 13(1), pp. 30–50. doi: 10.1080/2201473X.2021.2022900.

Wood, L., 2015. The environmental impacts of colonialism.

Younes, N., Yebra, M., Boer, M.M., Griebel, A. and Nolan, R.H., 2024. A review of leaf-level flammability traits in Eucalypt trees. Fire, 7(6), p.183.